Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

By Cmdr. Nolan V. Cain, U.S. Coast Guard, 12 January 2024

The Long Blue Line blog series has been publishing Coast Guard history essays for over 15 years. To access hundreds of these service stories, visit the Coast Guard Historian’s Office’s Long Blue Line online archives, located here: THE LONG BLUE LINE (uscg.mil)

With the Fast Response Cutter and National Security Cutter programs nearing completion, and the recent launch of the first Offshore Patrol Cutter, Argus, the Coast Guard is well on its way to recapitalizing the fleet with highly capable assets. Meanwhile, the two leading ships of the 210-foot Reliance-class cutters, Coast Guard cutters Reliance and Diligence, will turn 60 years old in June and August of this year, respectively. While ships of this vintage might otherwise be considered maritime museums, these iconic cutters and their dedicated crews continue to carry out Coast Guard lifesaving, law enforcement, and homeland security missions. The following is a look back at the beginning of Reliance and Diligence’s distinguished 60 years of service.

The decision to name the first two 210-foot cutters — Reliance and Diligence — came early in 1962. A study that concluded in November of 1961 evaluated more than 15 categories of names, including lakes, indigenous tribes, islands, seamounts, universities, historic cutters, and commandants. It was decided that the Reliance-class would include seven ships with historic names and the rest would take on names that, “connote action, aggressiveness, and daring.” Some of the initial suggested names were seen as too aggressive, and this direction was later amended to use names that were, “desirable human traits.” While some of the names on the list were adopted for the 210-foot cutters we know today, there were many that thankfully did not make the cut, such as, CGC Eager, CGC Lively, CGC Aggressive and CGC Timely.

It is no mystery why the lead ships were named so. The many preceding cutters bearing the names Reliance and Diligence were rich in heritage and service history. The current Reliance is the fourth so-called cutter, with the first being a steam tug commissioned in 1861 that saw service in the Civil War and was sold in 1865. The second Reliance was commissioned in 1867 and patrolled the waters of Alaska until it was decommissioned in 1876. The third Reliance was a 125-foot cutter built in 1927, during Prohibition, to interdict rumrunners and later refitted as a sub-chaser in World War II. The cutter was stationed in Honolulu, Hawaii, at the outbreak of World War II and attacked an enemy submarine near Johnston Atoll in 1944.

The current Diligence is sixth in a long line of cutters of the same name, beginning with one of the service’s original ten revenue cutters built in 1790. Built in 1798, the second Diligence was larger and could carry between 10 and 14 guns. This cutter was transferred to the U.S. Navy in 1799 to fight in the Quasi-War with France. Little is known of the third cutter Diligence other than it was lost in a hurricane in July of 1806 near Ocracoke Island, North Carolina. The following year, a fourth Diligence was built that saw action in the War of 1812 and was in service until 1831. The name was not used again until 1927, when the fifth cutter Diligence was commissioned. Like its sistership Reliance, Diligence’s main purpose was to stem the flow of illegal rum smuggling and it served until 1961.

In the early 1960s, America was a country on the brink of social and political change. The civil rights movement was in full swing, and the Cold War threatened global stability. The vibrant sounds of the Beatles and Motown dominated the airways, a fitting soundtrack to the start of dynamic decade. Art and design reached new heights with Googie architecture and the radical car designs from the Detroit automotive companies. One person in particular, Raymond Loewy, had a tremendous impact on industrial design the first half of the 19th century and continued to make his mark well into the 1960s. His repertoire included a wide variety of “streamlined” designs for furniture, kitchen appliances, automobiles, and trains, as well as the well-known Coca-Cola bottle, and even spaceship interiors.

In 1961, the Raymond Loewy and William Snaith design team took on the interior design of the Coast Guard’s first shipbuilding endeavor since World War II — the Reliance-class cutter. This ship design program included general arrangements of interior spaces, furniture, materials, and colors. The firm’s work in the area of ship interior design would lead to fundamental changes in habitability standards for U.S. Navy ships.

The Reliance-class cutters were originally designed with search and rescue as their primary mission. Requirements published in 1961 called for a cutter 210-feet in length with a 34-foot beam and equipped with a novel combined diesel and gas-turbine propulsion plant (CODAG), giving the cutter a cruising range of 5,000 miles at 15 knots. Special features included a flight deck large enough to land a Coast Guard Seahorse helicopter, a 360-degree visibility bridge, and exhaust piped through the stern. The contract was awarded to Todd Shipyard in Houston, Texas, which subcontracted a majority of the detail design to J.J. Henry, Inc., Naval Architects in Philadelphia.

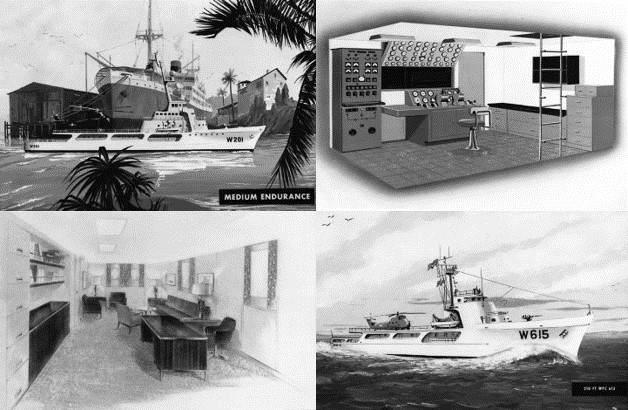

| Image may be NSFW. Clik here to view.  |

| Reliance-class cutter concept art with interior sketches from the Loewy/Snaith Design company. The artist for the ship profile is unknown. (Coast Guard Historian’s Archive) |

At the time, the Reliance-class’s construction materials and processes were state-of-the-art and included advanced epoxy protective coatings and noise reducing materials. The cutters equipment and general arrangements were designed to reduce personnel and maintenance requirements and best utilize available space. The cutters were not intended for wartime use but were equipped with a 3-inch, 50-caliber gun and space allocation was made for anti-submarine warfare equipment should the need arise.

Reliance was christened and launched on May 25, 1963, and Diligence held a similar ceremony on July 20, 1963. Both ships were commissioned the following year in June and August of 1964, respectively, beginning a new era for the Coast Guard cutter fleet. Initial plans called for as many as 30 Reliance-class cutters, but only 16 were built with the last, Alert, entering service in 1969. The ships performed favorably and were able to reach their target speed of 18 knots, however, the CODAG arrangement was difficult to operate and took up much of the engine room space. Only the first five cutters received the CODAG propulsion system, and the rest received Alco diesel engines. In the 1970s, the more reliable Alco engines became standard for the entire class.

Reliance proved its value to the fleet early on by providing a proof of concept for cutter helicopter operations. Up to this time, landing helicopters on cutters had been experimental and not part of standard operations. The Reliance-class cutters, along with their forthcoming bigger siblings, the Hamilton-class cutters, were designed with a helicopter landing pad. Because this capability was unproven, the future of cutter-based aviation hinged on the successful operational testing on the 210s. In preparation for the operational tests, a wooden grid was added on Reliance’s flight deck to stabilize the helicopter during landings by capturing the landing gear. Due to scheduling complications, initial cutter helicopter operations took place during Reliance’s sea trials, from July 7 to 10, 1964, off the coast of Galveston. During this three-day period, a HH-52 helicopter completed 170 landings, including 20 nighttime landings. A second set of flight-deck landings was scheduled in November of that year, this time in more challenging environmental conditions. At the conclusion of these evolutions, Reliance had proven that the Coast Guard was ready to advance shipboard helicopter operations.

Not to be outdone by her slightly older sister-ship, Diligence was soon pioneering a new concept as well. After a referral from President John F. Kennedy, the Coast Guard once again collaborated with the Loewy and Snaith team — this time to design a new service logo. In March of 1965, the design firm presented their ideas for the new service logo to senior leaders at Coast Guard Headquarters. Soon after, Diligence was chosen as one of the units to prototype the new logo, along with the cutter Androscoggin, several aircraft, and small boats. This design was later implemented service wide in 1967.

The 1960s was an exciting decade for space exploration. At the time, the “Space Race” was in full swing and by 1965 the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s (NASA) was ready to launch the third Gemini mission. Gemini III was the first crewed space mission for the Gemini program. CGC Diligence and her sister ship Vigilant, with attached HH-52 helicopters, joined the aircraft carrier USS Intrepid as part of the Gemini III capsule recovery force. The pilots that flew in the recovery operations were the same that had participated in the initial helicopter operational tests aboard Reliance. The Gemini III mission was launched on the morning of March 23, 1965, and splashed down approximately four hours later just short of the designated landing area. Diligence was first on scene and launched its helicopter to ensure the safety of the Gemini and crew. Sometime afterward, Navy helicopters from USS Intrepid recovered the astronauts. Although the Coast Guard was largely uncredited, this mission proved the versatility of the new class of cutter.

For Reliance and Diligence these early missions were just the beginning of six decades of service to our nation. These ships and the generations of crewmembers to cross their decks went on to launch daring rescues, pursue drug smugglers and poachers, responded to natural disasters, and remain to this day enduring symbols of U.S. sovereignty on the high seas. There are many newer and more sophisticated cutters in the Coast Guard’s fleet today; however, none can match the character and legacy of these two ships.

1964 : First of the 210 foot Coast Guard Cutters Were Launched

by John “Bear” Moseley, Coast Guard Aviation Association Historian

CGAA Historian”

Clik here to view.

A long range plan, suggested by the Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, to address the obsolescence of the cutter fleet was undertaken in 1959. The first cutters built under this plan were thirty six 95 foot patrol boats followed by seventy nine 82 foot patrol boats. Meanwhile the first postwar cutters were being designed to replace the 125 and 165 footers. They were the first cutters, designed from the keel up to facilitate helicopter operations. The helicopter landing platform required a minimum 200-foot waterline.

The initial concept of helicopter operations from cutters was pioneered by Frank Erickson during the Coast Guard development of the helicopter during World War II. Operation High Jump and subsequent Arctic and Antarctic operations demonstrated the value of the helicopter to the icebreaker. This concept, strongly supported by their Commanding Officers, did not carry over into the rest of the cutter fleet during this period. However, CAPT John P Latimer, a LT at the time, while attending postgraduate school after WWII, with assistance from CDR Frank Erickson and LTJG Art Pfeiffer, did a design project of a ship with a helicopter landing platform. It was about the size of the future Hamilton Class cutters with a configuration similar to the future Hamilton and Reliance Class. Latimer had consulted with Erickson and flew onto ships in a helicopter. His design provided for a helicopter deck and a hangar. Latimer said that he was surprised when he later served a tour in the Headquarters Engineering Section (ENE), that the design had received quite a bit of study by a couple of civilian architects. One of these gentlemen was Sam Frank, who was the senior civilian when the Reliance and then the Hamilton were designed. CAPT Gil Schumacher, Chief of ENE in 1962, with the assistance of CDR CG Houstma and Sam Frank, evolved and pushed through the design.

The outward appearance of these new cutters reflected the evolving nature of Coast Guard operations during the latter part of the 20th Century. They had sleek lines with the most prominent feature being the flight decks. They were originally fitted with transom exhaust ports that provided more room for a larger flight deck and kept the flight deck clear of exhaust smoke. In practice, however, the exhaust system proved problematic. Their high pilot house gave the bridge crew unrestricted all-around visibility, making ship-handling easier. A number of other concerns figured into the design phase including maximum serviceability, improved habitability, long service life, and safety. Two shafts capped by controllable pitch propellers drive these cutters to a top speed of 18 knots. The first five Cutters had a propulsion plant consisting of two 1,500 HP Cooper-Bessemer diesel engines and two 1,000 HP Solar Saturn gas turbines. The propulsion system could be remotely controlled from the pilot house, either bridge or wing, or the engine room control booth.

The construction of the 210 foot cutters to provide for helicopter operations was not without strong opposition on the part of some. With many it was an aversion to change but there were legitimate unknowns and problems to overcome. While the model of the vessel was given a thorough evaluation at the Taylor Model Test Basin in Washington D.C., only the characteristics as far as sea handling could be obtained. ENE was emphatic that they had no idea how the vessel would handle or reset with an 8500 pound helicopter on the flight deck. In addition, Sikorsky stated that under static conditions the HH52A helicopter, at normal gross weight conditions, would probably roll over after being tilted past 15 degrees.

Clik here to view.

There were three vessels under construction at Houston’s Todd Shipyard; the Reliance being first with the Diligence and the Vigilant not far behind. The helicopter-shipboard operations evaluation was conducted on the Reliance. Headquarters Office of Aviation (OAU), strongly in favor of the helicopter-ship concept, realized that should this vessel not be capable of operating safely with the HH-52A helicopter that the remaining WMEC cutters would be built without the flight deck. With this in mind the Commandant, at the behest of the Chief OAU, directed that a well qualified aviator experienced in open sea shipboard helicopter operations be assigned to assist the Commanding Officer of the Reliance in developing a capability for helicopter operations. LCDR John C. Redfield was selected for the assignment.

On May 15, 1964 LCDR Redfield met with CDR Frank Fisher, the prospective Commanding Officer of the Reliance, to discuss the up-coming tests and evaluation. In addition, Redfield obtained permission from Petroleum Helicopters to use their support facilities at the Galveston, Texas support facility. He further obtained the services of Lt William Russell to assist in the program. Russell, with the assistance of the Houston Air Station trained the Reliance crew in proper procedures and fire-fighting techniques. The sea trials were delayed until 7 July because of vessel machinery and yard problems. The vessel had a further commitment to be in the Coast Guard Yard, Baltimore, Maryland in early October. This resulted in the sea trials and helicopter operations being conducted simultaneously. LT. Russell was able to provide the crew with some preliminary training while the vessel was still in the shipyard. This was extremely important since the crew, almost to a man, from the officers on down, were new to ship-helicopter operations.

Preliminary evaluation of the helicopter on a metal deck aboard a Navy LST and previous experience aboard the Coast Guard icebreakers indicated the surface of the Reliance would have to be painted with abrasive paint and in addition some form of “chock” would have to be provided to assist in stabilizing the helicopter until the tie down equipment could be attached. The static stability of the helicopter on the helicopter deck required high tie down points affixed to the aircraft above the wheel shock-absorber housing. Extensions were fabricated to enable a person on the helicopter platform to “tie-down” and secure the helicopter. A wooden grid similar to those used by Petroleum Helicopters was designed to fit the Reliance flight deck and was constructed by Coast Guard Base Galveston.

On 6 July, with the permission of CDR Fisher, the HH-52A 1356 landed on board the Reliance while still tied to the dock. The aircraft was left on the deck, in proper position, in order to mark and paint the deck. On the morning of 7 July, the Reliance was underway and aircraft operations commenced when five miles off Galveston Beach. They continued intermittently for three days while the vessel underwent sea trials. Numerous landings were made by LCDR Redfield, LT Russell and Sikorsky pilot Mr. Bob Keim. On 10 July the Reliance moved off the Louisiana coast to conduct landings with a selected group of pilots from CGAS New Orleans to get their reaction and inputs to the rough draft of an operations bill for helicopter recovery. A total of 170 landings, 20 at night had been made. It was apparent that the Reliance was an excellent new concept for Coast Guard operations but it had yet to be tested in rough water weather operations.

Early in October, after the Reliance had completed work at the Coast Guard Yard, arrangements were made for rough water weather tests upon the arrival of the ship at Corpus Christi. Texas. CDR Frank Shelly, who had done the development and acceptance, flights for the HH-52 joined the group. On 19 November, with a good sea running and a brisk wind, the Reliance moved off shore. Five aviators flew the helicopter over a two day period on different wind and sea combinations. All landings were successful and LCDR Redfield stated that it was apparent that the Reliance had the desired characteristics for helicopter operations and was capable of working under sea conditions that were before impossible during wind class icebreaker operations. As a direct result of these test and evaluations the remaining WMEC 210’s and follow on cutters were designed for ship/helicopter operations.

The full utilization of the ship/helicopter was slow to develop. The 210’s had a crew of 70 and helicopter operations were labor intensive and helicopter operations, at that time, did not enjoy the full support of most of the Commanding Officers. The Air Stations were also reluctant to advocate full utilization as a deployment of a helicopter and crew would leave the duty sections short handed. No additional personnel were assigned to compensate for this. Training was conducted and limited SAR utilization took place but operational commitments were controlled by the District Commander and utilization was in direct proportion to his view point. The HQ Floating Units Section and the HQ Office of Aviation Units did not aggressively pursue the concept because they never envisioned at the time all of the uses for the ship/helicopter team. Drug enforcement was not a major factor in 1964 and there were not yet boat loads of people coming from Cuba. The Commander First Coast Guard District was the first to direct all ships capable of carrying a helicopter to do so while conducting fishery patrol and enforcement. The Coast Guard’s role in the Drug War started in 1976 and the Mariel Boat Lift in 1980. The helicopter/ship combination became indispensable to effectively carry out the mission. Today the concept is fully implanted in Coast Guard operations.

Each cutter underwent a “Major Maintenance Availability” process, or MMA, between 1986 and 1996 at a cost of between 19 and 21 million dollars per cutter. Every cutter received the following modifications and upgrades: improved habitability, improved stability by rearranging tank locations, replacement of all asbestos paneling, increased the berthing space, upgraded the flight deck and helicopter equipment, increased the amount of helicopter fuel carried, improved the evaporator, increased and upgraded the communications and electronics capacities, installed vertical exhaust stacks and associated ballast, and installed a smoke detection system and new fire-fighting equipment.

In the course of Coast Guard history there are numerous things that have been done well that directly affect and improve upon Coast Guard operations. Some of these accomplishments acquire a much greater significance than imagined at the time they were accomplished. Such was the case with LCDR John Redfield. In addition to being a people person who was extremely competent he had the capability to innovate and solve unforeseen problems effectively. The successful evaluation and implementation of the ship/helicopter concept was due largely to his efforts. Without this success the remaining cutters in the immediate building program and those that followed would have been built without helicopter capabilities. Without this capability the Coast Guard would have been significantly restricted in operational capabilities during the years that followed.